진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질에 대한 통합적 고찰

An Integrative Review of Health-related Quality of Life in Patients with Advanced Heart Failure

Article information

Abstract

Purpose: Even though advanced heart failure (HF) severely affects the patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQoL), there is little information regarding this issue. This review is aimed to describe the relevant clinical characteristics of patient with advanced HF and identify factors influencing HRQoL in these patients. Methods: Empirical articles were searched from electronic databases issued from January 2000 to June 2018 with using the key terms ‘heart failure’ and ‘quality of life’. There were a total of 22 articles that met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed for this study. Results: First, nine studies among 22 studies clearly stated that their participants were samples of patients with advanced HF. Most reviewed studies showed the New York Heart Association (NYHA) class as the criteria for identifying advanced HF. Second, the level of HRQoL varied depending on the measurement tools utilized by the researchers. Third, the NYHA class, gender, and symptoms were mainly associated with HRQoL in patients with advanced HF. Also, nurse- or physician-led intervention, exercise, spiritual-focused intervention, and palliative care improved the HRQoL of the patients with advanced HF. Conclusion: This study found that the clear application of criteria for advanced HF and the development of advanced HF-specific HRQoL measurement was needed. Prospective studies should be considered for identifying differences in the levels and factors influencing HRQoL in patients with early stage or advanced HF to design patient-centered care.

서 론

1. 연구의 필요성

심부전(Heart failure, HF)은 진행성 비가역적 만성 질환으로, 심 장 구조이상 또는 심장 기능의 문제로 인해 심장이 신체에 필요한 만큼 혈액을 충분히 박출하지 못하여 조직의 대사요구를 충족시키 지 못한다[1]. 최근 급속한 인구 고령화와 관상동맥질환을 포함한 심혈관계 질환의 만성화로 인해 선진국을 비롯하여[2] 국내에서도 심부전 유병률은 점차적으로 증가하고 있다[3].

심부전의 중증도는 주로 미국 뉴욕 심장협회(New York Heart Association, NYHA)에서 제시한 분류단계로 구분하는 데[4], 환자의 증상호소와 신체활동 능력에 따라 4단계로 나뉜다. 1단계는 일상적 인 신체활동에 제한이 없고 심부전 증상이 없는 상태를 말하며, 2 단계는 휴식 시에는 증상이 없으나 일상적인 신체활동시 증상이 나타나 신체활동에 약간의 제약이 있는 경우, 3단계는 일상적인 신 체활동보다 낮은 수준의 활동 시에도 증상이 있어 신체활동에 뚜 렷한 제한이 있는 상태, 마지막으로 4단계는 휴식 시에도 증상이 나 타나며 활동시 더욱 악화되고 일상활동에 심각한 제한이 있는 상 태이다[4]. 최근에는 심부전으로의 진행을 조기에 예방하는 데 초 점을 두어 미국 심장학회(American Heart Association, AHA)에서 제 시한 Stage A, B, C, D로 심부전 중증도를 나누기도 한다[5]. Stage A는 심부전 증상 및 구조적 심장질환이 없는 경우, Stage B는 심부전 증 상과 징후는 없으나 구조적 심장질환이 있는 경우, Stage C는 구조 적 심장질환이 있는 상태에서 심부전 증상이 나타난 경우, Stage D 는 최적의 심부전 치료에도 증상이 심한 상태를 말한다. 따라서 진 행성 심부전(advanced HF)은 적절한 치료에도 불구하고 치료 효과 가 나타나지 않고 증상이 지속되거나 심해지는 상태로 흔히 말기 심부전(end-stage HF) 또는 불응성 심부전(refractory HF)이라는 용 어로도 혼용되며, NYHA 3-4단계와 Stage D를 의미한다[5]. 특히 초 기 심부전 환자에 비해 진행성 심부전 환자는 1년 내 사망률이 약 30% 이상으로 보고되고 있어[6], 무엇보다 적극적인 관심과 질병 중 증도를 반영한 중재전략이 요구된다.

현재, 심부전 치료에 사용되는 약물들의 효과가 개선되고 기계 보조장치가 눈부시게 발전되고 있음에도 불구하고, 심부전 환자에 서 건강관련 삶의 질 저하는 주요 임상문제로 남아 있다[7,8]. 즉, 적 절한 치료에도 불구하고 심부전 증상이 악화되면 일상생활조차 유 지가 어려워, 잦은 응급실 방문 및 재입원으로 이어지고 건강관련 삶의 질 저하를 초래한다[2,9]. 지금까지 심부전 환자 대상 연구는 주로 심실기능을 보조해주는 약물적/비약물적 치료의 임상적 효 과를 판단하기 위한 연구가 다수였으나, 최근에는 심부전 환자의 건강결과로서 재입원률과 사망률 뿐 아니라, 건강관련 삶의 질 개념 이 중요한 측정변수로 주목받고 있다[10,11]. 그러나 대부분의 선행 연구들이 심부전 초기 환자를 대상으로 하였거나, 심부전 중증도 를 구체적으로 명시하지 않아, 초기 심부전 환자의 치료방향 및 목 표를 동일한 내용으로 진행성 심부전 환자에게 적용하기는 어렵다 [11]. 진행성 심부전 환자를 대상으로 한 연구는 이에 대한 정의가 정 립되기 시작한 2000년 이후부터 이루어지기 시작하였으나[12,13], 주로, 이들 대상의 건강관련 삶의 질에 대한 측정은 약물효과를 보 기 위한 변수로만 활용되었다[14]. 또한, 진행성 심부전의 정의가 각 연구들마다 다소 차이가 있어 각 연구결과들을 통합하기 어렵고, 그에 따른 사망률과 건강관련 삶의 질 등에 관한 선행연구결과 간 의 차이도 큰 것으로 나타났다[5,6,12]. 특히, 지금까지 보고된 심부 전 환자의 삶의 질 관련 문헌고찰 연구는 심부전 단계를 구분하지 않고 있어, 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질에 대한 수준 및 영향요인을 확인하는 데 있어 한계가 있다[10,11,15].

최근 임상실무에 적용할 수 있는 과학적인 근거 생산의 중요도 가 높아지면서, 특정 주제에 대한 여러 연구결과들을 분석하여 추 후 연구 및 활용 방안을 제시하는 문헌고찰 연구가 다양하게 이루 어지고 있다[16,17]. 이 중 Whittemore와 Knafl [18]가 제시한 통합적 고찰(Integrative review)은 연구주제에 대한 다양한 일차 연구들을 종합하고 분석하여 연구문제에 대한 전체적인 이해와 함께 새로운 개념을 설정하거나, 폭넓은 결론과 새로운 방향을 이끌어낼 수 있 는 문헌고찰 방법론이다. 즉 특정 연구주제에 대한 연구결과만을 확인하는 체계적 고찰연구에 비해 통합적 고찰은 다양한 연구결과 를 합성하여 심도깊은 내용으로 제공할 수 있다는 장점이 있다[19].

따라서 본 연구는 진행성 심부전 환자의 특성을 파악하고 이들 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 수준과 관련 영향요인을 통합적으로 파악 함으로서 진행성 심부전 환자에 대한 폭넓은 이해를 돕고자 한다.

2. 연구목적

본 연구의 목적은 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질에 대 한 기존 선행연구들을 통합적으로 고찰함으로서, 향후 이들 대상 자의 건강관련 삶의 질 개선을 위한 간호중재 개발 시 기초자료로 활용하고자 함이다.

연구 방법

1. 연구설계

본 연구는 진행성 심부전 환자를 대상으로 건강관련 삶의 질의 수준 및 영향요인을 확인하기 위해 Whittemore와 Knafl [18]의 방법 으로 수행한 통합적 고찰연구이다.

2. 연구 대상

본 연구는 Whittemore와 Knafl [18]의 통합적 고찰 방법론에 따라 5단계로 진행되었다.

첫 번째는 연구문제 확인 단계로, 연구문제와 문헌고찰 목적을 명료히 제시하여 탐색하고자 하는 개념과 적절한 표본을 결정하는 단계이다. 두 번째는 문헌검색 단계로, 잘 정의된 문헌검색 전략[20] 을 통해 연구문제에 적절한 모든 선행 연구를 찾아내는 단계이다. 세 번째는 자료평가 단계로, 통합적 고찰에 포함되는 일차 연구들 의 질을 평가하는 단계이다. 다양한 일차 연구가 포함될 수 있는 통 합적 고찰의 특성상 일차 연구들의 질을 평가하는 정형화된 방법 과 도구는 없기에, 어떤 연구들이 포함되었는지에 따라 적절한 질평 가 도구를 사용하는 것이 중요하다[21]. 네 번째는 자료분석 단계로, 통합적이고 편견없이 자료를 추출해내고 의미를 파악하는 단계이 다. 연구문제에 기반한 논리체계를 통해 일차 연구들로부터 자료를 추출하여 연구문제에 대한 설명을 제시하고 모든 일차 연구들을 포괄하는 결론을 내린다. 이를 위해 자료의 패턴 파악, 클러스터링, 대조 또는 비교해보기, 변수들 간 관계 파악, 중재요소 파악, 새로운 논리관계 정립 등의 과정이 수행될 수 있다. 다섯 번째는 자료 표현 단계로, 통합적 고찰을 통해 제시되는 개념이나 속성을 표나 그림 으로 표현하는 것이다. 각 단계에 따른 구체적인 연구절차는 다음 과 같다.

1) 연구문제 확인

본 연구를 관통하는 연구 질문은 “진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관 련 삶의 질은 어떠한가?”이다. 이를 위한 주요 연구 문제는 “진행성 심부전 환자의 질병관련 특성은 무엇인가?”와 “진행성 심부전 환자 의 건강관련 삶의 질 수준 및 영향요인은 무엇인가?”이다. 진행성 심 부전의 이론적 정의가 일차 연구들에서는 어떻게 정의되었지 확인 하고 연구대상자의 건강관련 삶의 질을 파악함으로서 추후 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 향상 중재개발을 위한 과학적 근 거를 제공하고자 한다.

2) 문헌검색

자료수집을 위한 검색 database는 Pubmed, Embase, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), PsycArticles, Cochrane이었다. 구체적인 선정 기준은 1) NYHA 3-4단계 또는 AHA stage D로 정의되는 진행성 심부전 환자를 대상으로 하였거나 제목 또는 연구대상에 진행성 심부전(advanced HF)을 명시한 연구, 2) 건 강관련 삶의 질을 독립 또는 종속 변수로 제시한 양적 연구, 3) 영어 로 출판된 연구, 4) 성인을 대상으로 한 연구, 5) 진행성 심부전의 개 념이 정립되기 시작한 2000년부터 2018년 6월까지 발표된 연구이다. 배제 기준은 1) 연구 유형이 종설이거나 측정도구 개발, 연구 프로 토콜, 학술대회 발표자료 등 원저가 아닌 경우, 2) 약물적 중재에 따 른 건강관련 삶의 질 비교 연구인 경우, 3) 치료 또는 시술의 효과를 보기 위한 결과변수로서 건강관련 삶의 질 연구인 경우, 4) 연구대 상자의 제외 기준으로 NYHA 4단계가 명시된 경우이다.

논문 검색에 사용된 주요어는 ‘heart failure’와 ‘health related quality of life’이나, 이들 용어가 각 연구들에서 다양하게 표현됨에 따라 ‘heart failure’는 cardiac failure, congestive heart failure, chronic heart failure, systolic dysfunction, diastolic dysfunction을 검색조건에 포함 하였고, ‘health related quality of life (HRQoL)’는 quality of life, patient reported outcome (PRO), patient reported outcome measures, symptom, functional status와 약어인 HRQoL, PRO를 검색조건에 포함하 여 광범위하게 검색하였다. 특히, 각 논문에서 제시되는 진행성 심 부전의 정의가 동일하지 않은 형식이기 때문에, 진행성(advanced) 혹은 말기(end-stage)라는 단어를 사용하지 않아 검색되지 않는 것 을 방지하기 위해 초기 검색 조건에서는 ‘advanced’ 혹은 ‘end-stage’ 를 포함하지 않았다. 그리고 건강관련 삶의 질 영향요인과 효과 있 는 비약물적 중재방안을 모두 고찰하기 위해, 양적 연구 내 구체적 인 연구방법론은 제한하지 않았다.

문헌 검색과 선정과정은 PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis)의 체계적 문헌고찰 흐름도[22] 에 따라 진행하였다. 검색엔진을 통한 1차 문헌검색 결과 총 6,279편 의 문헌이 검색되었고, 이 중 중복된 1,890편을 제외한 4,389편의 제 목과 초록을 검토하여 선정기준에 부합되지 않는 3,805편(원문검색 이 안되거나 해당 주제 아님)을 제외하고 584편을 선정하였다. 584 편의 원문을 검토한 결과, 연구대상에 NYHA 1-2단계가 포함된 290 편, 건강관련 삶의 질이 주요 변수가 아닌 65편, 비약물적 중재가 아 닌 157편, 원저가 아닌 논문 50편 등 총 562편을 제외하고, 22편의 문 헌(중재연구 9편 포함)을 통합적 고찰 대상 일차 연구로 선정하였다 (Figure 1).

3) 자료평가

최종 선정된 22편의 연구는 조사연구와 실험연구가 포함되어 있 으므로 Joanna Briggs Institute(JBI) checklist [23]를 이용하여 조사연 구(JBI critical appraisal checklist for observational studies)와 실험연구 (JBI critical appraisal checklist for experimental studies)에 대한 질 평 가를 각각 시행하였다. 두 명의 연구자가 독립적으로 질 평가(yes= ○, no 또는 unclear= ×)를 실시하였고, 연구자간 일치하지 않은 항 목에 대해서는 심도 있는 논의를 통해 합의된 결론을 도출하였다. 그 결과, 논문의 선정과 제외 기준에 부합된 22편 중 관찰연구 13편 은 최대 5점 만점에 5편이 4점, 7편이 5점으로 나타나 대부분의 항 목을 준수하였다. 중재연구 9편은 최대 11점 만점에 5점인 연구 1편 을 제외하고 8편 모두가 과반수 이상의 항목을 준수하고 있었다. 단, 5-6점으로 평가된 중재연구 4편은 단일군 중재(A17, A20)이거나 연구 목적에 의해 무작위 맹검 조건이 어려운 연구(심부전 유형에 따른 중재의 효과를 본 A16, 영적 상담 중재이기에 대상자의 선호도 를 반영한 A19)인 것으로 판단되어 본 연구에 최종적으로 22편 모 두를 포함하였다.

4) 자료 분석

총 22편의 논문에 대해 조사연구와 실험연구로 나누어 자료를 추출하고 엑셀에 코딩하여 자료를 축소하였다. 즉, 조사연구와 실험 연구로 구분하여 발표 연대순으로 배열하고, 대상자 선정기준, 대상 자 분포, 대상자 나이, 대상자 임상 특성(NYHA 중증도 단계, 좌심 실박출계수, 약물 및 device 치료 여부), 연구 설계, 건강관련 삶의 질 측정 시점과 측정 도구, 건강관련 삶의 질 수준, 주요 연구결과를 요 약하였다. 이를 바탕으로 진행성 심부전 환자의 특성, 각 연구별 의 미 있는 내용을 구분하여 자료를 표시하였다. 건강관련 삶의 질 영 향요인으로 도출된 변수들은 심부전 환자에서 삶의 질의 영향요인 에 대한 개념적 모델[24]에 따라 체계적으로 자료를 합성하였다.

Rector [24]의 삶의 질 모델은 심부전 환자의 삶의 질에 대한 개념 적 혼란을 정리하고 과학적인 틀을 제공하기 위한 목적으로 정립된 것으로, 본 연구의 진행성 심부전 환자 대상 건강관련 삶의 질의 영 향요인을 분석하기 위한 틀로서 적절한 모델이다.

5) 자료제시

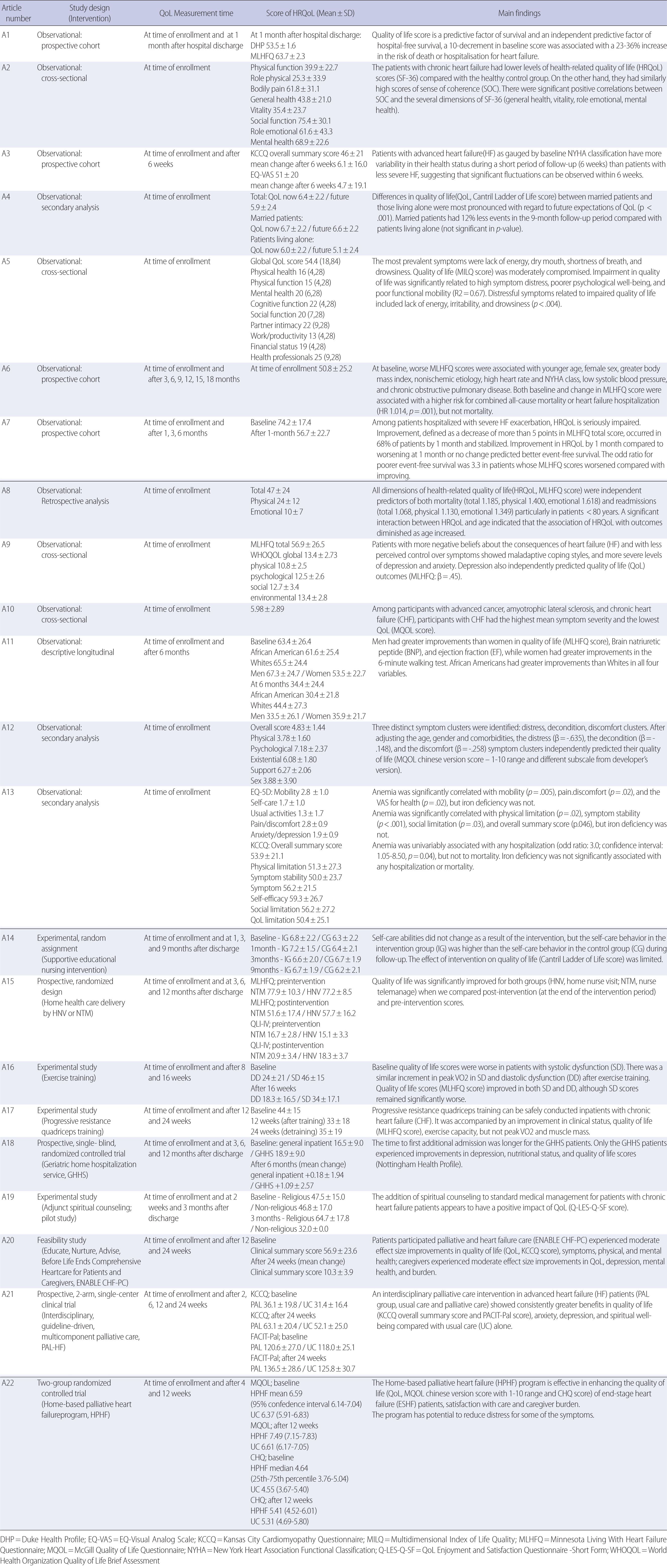

진행성 심부전 환자의 특성과 건강관련 삶의 질 수준 및 측정 도 구를 Table 1-3과 같이 정리하였으며, Rector [24]의 삶의 질 모델을 바탕으로 건강관련 삶의 질 영향요인을 심부전 병태생리, 증상, 기 능제한, 심리적 디스트레스, 외생 요인의 5개 요인으로 분류하였다 (Table 4).

연구 결과

1. 진행성 심부전 환자의 특성

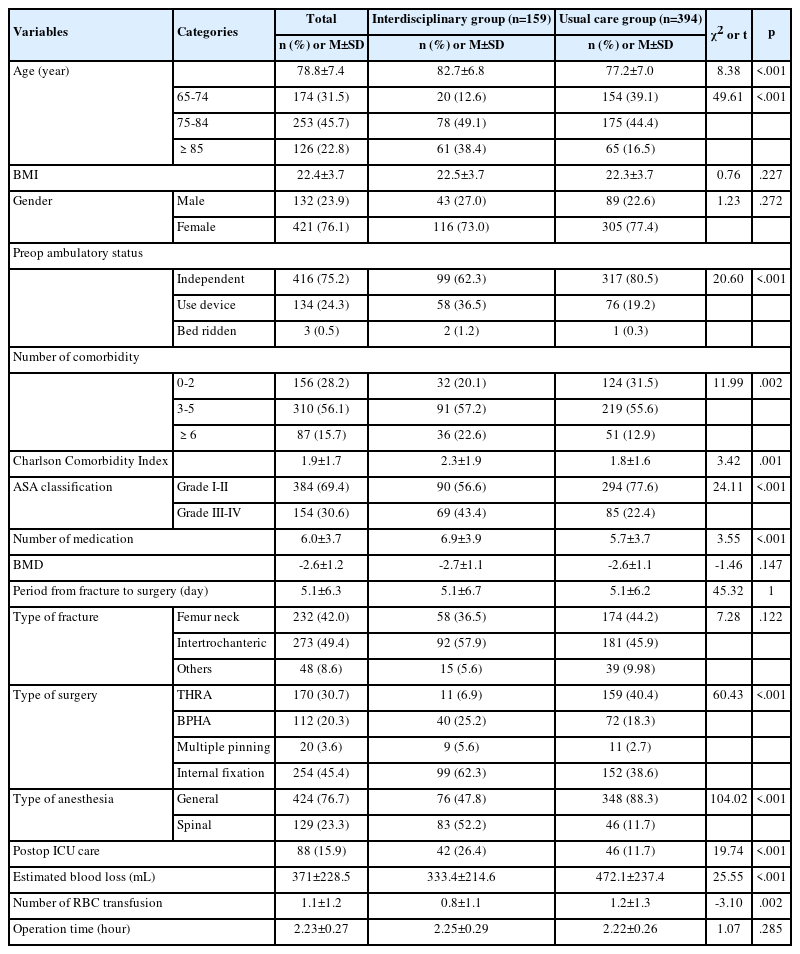

본 연구를 통해 제시된 진행성 심부전 환자의 특성은 Table 1과 같 다. 총 22편 중 9편만이 연구제목과 연구목적에 진행성 심부전 환자 를 대상자로 명시하였고, 대부분의 연구에서 심부전 대상자 선정기 준으로 NYHA 중증도 단계만을 제시하고 있었다. 연구대상자의 NYHA 중증도는 모두 3단계 또는 4단계였고, 6편[Appendix: A3, A6, A8, A10, A13, A22]만이 증상이 지속되거나 지난 3-6개월 동안 NYHA 중증도 3단계 이상이거나 이로 인해 입원한 환자임을 명시하였다. 입 원 환자를 연구대상자로 포함한 경우가 13편(59.1%)으로 많았고, 대 상자들의 평균 나이는 48.6-82.9세였다. 좌심실 박출계수의 평균 수 준은 19.6-55.0%까지 다양하였다. 연구대상자들이 복용하는 약물 종 류에 대해 12편(54.5%)의 논문이 보고하였으나 기계보조 장치(좌심 실 수축력을 증가시키는 경피적 좌심실 보조 장치와 삽입형 심실보 조장치, 위협적인 심실 부정맥을 방지하는 삽입형 제세동기 등)의 사 용 여부는 5편(22.7%)만 보고하였다. 연구대상자 수는 10명부터 1050 명까지 다양했으며 남성 환자의 비율이 50% 이상을 차지하였다.

2. 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 측정도구

22편의 분석대상 논문에서 총 15개의 건강관련 삶의 질 측정도구 가 사용되었으며, 일반적 도구(generic)와 질병 특이형 도구(disease-specific)가 따로 혹은 함께 사용되었다(Table 2).

가장 많이 사용된 건강관련 삶의 질 측정도구는 질병 특이형인 Minnesota Living With Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ)로 9편 의 논문에서 사용되었고, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ)와 McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire (MQOL)이 각 각 3편, 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)와 Cantril Ladder of Life이 각각 2편의 논문들에서 사용되었다. 일반적 도구와 질병 특 이형 도구를 함께 사용한 논문은 6편[A1,A3,A9,A13,A16,A22]이었 고, 이 중 3편이 MLHFQ를, 2편이 KCCQ를 질병 특이형 도구로 사 용하였다.

3. 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 수준

분석대상 연구들에서 제시된 건강관련 삶의 질 수준은 Table 3과 같다. 다빈도 측정도구별 건강관련 삶의 질 수준을 살펴보면, MLHFQ를 사용한 논문에서는 평균 47.0-74.2점 (0-105점 범위, 점수 높을수록 건강관련 삶의 질 낮음), KCCQ를 사용한 논문에서는 평 균 46.0-53.9점 (0-100점 범위, 점수 높을수록 건강관련 삶의 질 높 음), MQOL을 사용한 논문에서는 평균 4.83-6.59점 (1-10점 범위, 점 수 높을수록 건강관련 삶의 질 높음)이었다.

건강관련 삶의 질 수준 변화를 추적 조사한 논문은 14편으로, 중 재연구 9편의 경우 최소 3개월 이상 추적조사를 시행하였다. 특히 중재연구 1편을 제외한 나머지 13편 모두, 자료수집 초기의 건강관 련 삶의 질 수준보다 추적 조사 시의 삶의 질 수준이 높은 점수를 보였다.

4. 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 영향요인

본 연구에서 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 영향요인은 총 16개의 변수가 제시되었으며, 이를 Rector [24]의 심부전 환자 삶 의 질 개념 모델에 따라 5개 요인으로 구분한 결과는 Table 4와 같다.

첫째, 심부전 병태생리 요인에 해당되는 변수인 심부전 원인 (허 혈손상이 아닌 경우), 심박동수 (높은 경우), 기능부전의 유형( 수축 기 기능부전인 경우), 수축기 혈압 (낮은 경우), 빈혈 (있는 경우)에 따라 건강관련 삶의 질이 유의하게 낮은 것으로 나타났다. 둘째, 증 상 요인에 해당되는 변수인 증상 디스트레스 (높을수록)와 증상 클 러스터 (부정적인 증상일수록)에 따라 건강관련 삶의 질이 통계적 으로 유의하게 낮은 것으로 나타났다. 셋째, 기능제한 요인에 해당 되는 변수인 NYHA 중증도 분류 (높을수록)와 기능적 움직임 (좋 지 않을수록)에 따라 건강관련 삶의 질이 통계적으로 유의하게 낮 은 것으로 나타났다. 넷째, 심리적 디스트레스 요인에 해당되는 변 수인 심리적 웰빙 (좋지 않을수록)과 우울 (있는 경우)은 건강관련 삶의 질이 통계적으로 유의하게 낮은 것으로 나타났다. 다섯째, 외 생 요인에 해당되는 사회 인구학적 변수인 나이 (어릴수록), 성별 (여 성), 결혼상태 (결혼을 안 한 경우), 인종 (아프리카계 미국인인 경 우), 체질량지수 (높을수록), 동반질환 (만성폐질환)에 따라 건강관 련 삶의 질이 통계적으로 유의하게 낮은 것으로 나타났다. 실험 연 구인 경우 간호사와 의사가 적극 개입한 중재와 운동 및 영적 상담 중재, 완화간호가 건강관련 삶의 질을 통계적으로 유의하게 향상시 킨 것으로 나타났다.

종합하면, 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질은 개념적 모 델[24]에서 제시된 주요 4개 요인과 함께 외생 요인에 의해서 직접적 영향을 받았고, NYHA 중증도 단계와 성별, 증상이 다빈도 변수로 나타났다. 주요 4개 요인에 개선을 가져올 수 있는 중재(의료진의 개 입으로 적극적 증상관리, 운동 중재를 통해 기능 상태 증진, 영적 상 담 또는 완화 간호를 통해 심리적 안정 증진)는 건강관련 삶의 질을 향상시켰다.

논 의

본 연구는 진행성 심부전 환자의 질병관련 특성 및 건강관련 삶 의 질 수준과 영향요인을 파악하기 위해 관련 논문을 통합적으로 고찰하였다. 먼저 심부전 환자의 질병관련 특성에 관한 연구결과, 진행성 심부전 환자 진단기준으로 NYHA 중증도 분류체계가 가장 많이 사용되었다. 그러나 분석대상 논문 다수가 연구대상자를 심 부전 진단을 받은 자로만 기술하였고, 진행성 심부전 환자로 구분 하여 명시한 논문은 9편에 불과하였다. NYHA 중증도 단계는 주요 심부전 증상과 신체활동 제한정도를 기준으로 한 주관적 판단이 므로 최근 국내·외 심장관련 학회에서는 NYHA 중증도 단계 이외 에 좌심실 박출계수, 최고 산소섭취량(peak VO2), 강심제의 지속적 인 투여 여부, 저나트륨혈증이나 신부전 여부 등의 객관적인 기준 을 통해 초기 심부전 환자와 진행성 심부전 환자를 구분하여 제시 하도록 보고하고 있다[25]. 특히, 급성으로 심부전이 악화된 경우, 악 화 당시 NYHA 중증도가 4단계로 분류되었더라도 적절한 치료에 따라 증상이 개선되었다면, 이후 계속해서 진행성 심부전 환자로 분류하기는 어렵다[25]. 그러나 최근, 진행성 심부전 환자들의 임상 적 특징이 초기 심부전 환자와 비교하여 구분될 수 있는 특성으로 밝혀짐에 따라 보다 더 객관적인 임상특성을 중심으로 두 그룹을 구분하고자 하는 노력이 이루어지고 있다[5]. 따라서 초기 심부전 환자와는 다른 진행성 심부전 환자만을 특정지을 수 있는 객관적 인 기준을 적용하기 위한 지속적인 노력이 요구된다.

진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 수준과 영향요인을 살펴 본 결과, MLHFQ로 측정한 평균 건강관련 삶의 질 점수는 47.0-74.2 점이었다. 국내 심부전 초기 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질에 관한 고찰 [11]에서 동일한 측정도구로 평균 21.3-48.2점의 범위인 것과 비교하 면, 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질은 심부전 초기 환자보 다 현저히 저하되어 있음을 알 수 있다. 따라서 진행성 심부전과 심 부전 초기 환자의 명확한 분류를 통해 각 대상자의 질병특성에 맞 는 맞춤형 간호중재 및 치료전략이 건강관련 삶의 질 향상에 필수 적이다. 실제, 분석대상 연구 중 진행성 심부전 환자와 다른 말기 질 환 환자의 삶의 질을 비교한 결과[A10]에서도 진행성 심부전 환자 의 삶의 질이 현저히 낮은 결과를 보였다. 해당 연구에서는 증상이 삶의 질에 가장 큰 영향 요인으로 나타났으므로 증상 중증도가 가 장 높았던 진행성 심부전 환자의 삶의 질이 가장 낮은 것으로 설명 하였다. 또한, 분석대상 연구들 중 건강관련 삶의 질 향상에 효과가 있었던 중재연구[A15-A22]는 의료진의 적극적인 개입으로 대상자 에 맞는 관리전략을 적절한 시점에 수립할 수 있었던 것이 핵심이었 다. 따라서, 진행성 심부전 대상자와 가족 및 의료진 간의 심도 깊은 의사소통을 통해 대상자와 가족의 선호도와 의견이 반영된 완화간 호와 생명 연장치료 등의 삶의 질 개선을 위한 다각적인 활동을 계 획하는 것이 중요하겠다[26].

그러나 분석대상 논문들에서 각기 다른 건강관련 삶의 질 측정 도구를 사용하고 있어, 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 수 준을 객관적으로 비교분석하기는 어려웠다. 건강관련 삶의 질 수준 의 경우 실제 점수는 낮더라도 환자가 어떻게 병을 인식하느냐에 따라 삶의 질의 의미는 달라질 수 있다. 즉, Klindtworth 등[26]의 연 구에서는 진행성 심부전 환자라도, 환자 스스로 상태호전을 위해 노력하고 모든 치료방향을 알고 싶어 하는 등 긍정적인 인식을 보 고하였다. 그러나 Stocker 등[29]은 진행성 심부전 환자 대부분 자신 의 질병을 말기로 인식하지 않아, 완화치료에 대해 거부반응을 보였 다고 하였다. 따라서 진행성 심부전 환자를 간호하는 의료진은 치 료목표를 환자와 환자가족과 함께 설정하되, 환자마다 질병에 대한 인식이 다를 수 있음을 고려해야겠다. 또한 진행성 심부전 특징과 삶에 대한 영향력을 다각적으로 파악할 수 있는 진행성 심부전 특 이형 건강관련 삶의 질 측정도구의 개발이 요구된다.

본 연구에서 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질에 영향요인 으로 성별, 연령, 사회경제적 요인 (결혼상태), 동반질환, 증상 정도, 기능적 움직임, NYHA 중증도, 우울 등이 나타났다. 이는 전체 심부 전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질에 대해 고찰한 선행연구[15]와 거의 일 치하였다. 특히, Baert 등[15]에서도 우울, NYHA 중증도, 성별은 가 장 일치된 연구결과를 보인 변수들로 보고되었는데, 본 연구에서도 NYHA 중증도, 성별, 증상 정도가 주요 변수로 나타났다. 여성 심부 전 환자의 경우 남성 심부전 환자보다 건강관련 삶의 질 저하 정도 가 큰데 이는 신체적 원인과 함께 사회경제적 요소로 설명되고 있 다[27]. 즉, 남성보다 여성이 배우자와 헤어진 상태로 혼자 사는 경우 가 많고 사회경제적 지위가 낮은 경우가 많기 때문에 건강관련 삶 의 질에도 부정적인 영향이 있다는 것이다. NYHA 중증도의 경우, 증상 정도와 직결되는 개념이므로 건강관련 삶의 질 뿐 아니라 사 망률이나 재입원률 등의 임상결과에서도 중요한 영향요인이다[28]. Baert 등[15]은 대상 환자를 안정 단계의 울혈성 심부전 환자로 제한 하였으므로 본 연구에서 분석한 논문과 기준이 다르다. 더욱이, 진 행성 심부전 관련 연구가 절대적으로 적음에도 체계적 문헌고찰로 수행된 선행연구[15]의 결과와 동일한 변수가 도출된 것은 의미 있 는 결과이다. 따라서 심부전 환자라면 우울 증상 여부, NYHA 중증 도 단계, 성별에 따라 건강관련 삶의 질이 다를 수 있는데, 진행성 심 부전 환자라면 NYHA 중증도 단계와 성별에 따른 건강관련 삶의 질 차이의 가능성을 특히 염두에 두어야 할 것이다.

한편, 본 연구결과에서는 심부전 병태생리 요인에 해당하는 심부 전의 원인, 기능부전 양상, 심장 기능 상태가 건강관련 삶의 질에 직 접적으로 유의하였다. 그러나 Rector [24]의 심부전 삶의 질 개념적 모델에서는 증상, 기능제한, 심리적 디스트레스 요인만 삶의 질과 직접적인 관련성이 있음을 제시하였고 심부전 병태생리는 간접적 관련성으로 표현하였다. 본 모델에서는 진행성 심부전의 특징이 고 려되지 못하였으므로, 진행성 심부전 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 영 향요인에 대한 추후 연구를 통해 도출된 요인들을 검증하고 심부전 초기 환자의 건강관련 삶의 질 영향요인과 차이를 파악하는 것이 필요하겠다.

결 론

본 연구는 진행성 심부전 환자의 질병관련 특성을 파악하고 건 강관련 삶의 질 수준과 영향요인을 파악하기 위해 실시되었다. 연구 결과, 진행성 심부전 환자 대상임을 명확히 제시한 논문은 9편뿐이 었고 주요 기준은 NYHA 중증도 단계였다. 본 연구에서 도출된 주 요 건강관련 삶의 질 영향요인은 NYHA 중증도 단계와 성별, 증상 경험으로 나타났으며, 의료진이 적극 개입한 중재와 운동 및 영적 상담 중재, 완화간호가 건강관련 삶의 질을 유의하게 향상시킨 것 으로 나타났다.

본 연구를 통해 진행성 심부전 환자를 구분하는 진단기준이 명 확히 제시되고 현장에서 체계적으로 적용되어야 하며, 진행성 심부 전 환자의 질병특성을 고려한 질병특이형 건강관련 삶의 질 측정도 구 개발이 필요함을 확인할 수 있었다. 따라서 심부전 초기 환자와 진행성 심부전 환자 간 건강관련 삶의 질 수준과 영향요인에 어떠 한 차이가 있는 지 확인하기 위한 장기간의 전향적 코호트 연구가 후속 연구로서 필요하겠다.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.